Most experts agree that shared parenting is in the best interests of the child. There are also concerns that shared parenting is not the best arrangement for every family, including where family abuse is found, although some studies show that shared parenting is better for children in almost all situations. Find out below what the leading experts have to say about the outcomes of shared parenting for children.

Note: Some of the research into shared parenting has sparked a lot of controversy and contention. This is largely linked to research being misquoted, questions about the methodology of studies and the difficulty of comparing research that define shared parenting in different ways. Be sure to take care when reading about research online.

Outcomes For Children

Living Conditions

A Swedish study assessed how parenting arrangements can influence a child’s wellbeing & life experiences. These were measured in several categories including economic, social, health, working conditions & safety at school and leisure time activities.

Researchers found that in several areas, particularly in economic outcomes, children were slightly worse off living with one parent as opposed to children living with shared parenting or children living with both parents in the same household.

Children living with one parent as opposed to shared parenting or two parent families were also:

- More likely to report not getting on well with their parents

- Less likely to report their parents had time for them

- Reported worse peer relations including being less likely to claim having at least one close friend in class

- More likely to report less than good on a self-rated health scale and report smoking weekly far more frequently

- Assessed their school performance as being lower in relation to their peers

- Less likely to participate in organised sport activities on a weekly basis

Of course, many of the positive outcomes of shared parenting are also dependent on how parents execute these arrangements, not only the allocation of equal time. See our section on Quality Vs Quality for more information.

Watch Dr Malin Bergström talking about her research into the outcomes of shared parenting for children.

A Child-Centred Approach

Experts suggest that separated parents must think carefully to ensure they serve their children’s needs and put these above their own. Parenting arrangements should not be about Mothers’ rights against Fathers’ rights. See our section on conflict as a barrier to shared parenting for more information on this.

Shared parenting must reduce day to day stress for children while ensuring they feel safe, comfortable and providing meaningful, consistent relationships with their parents. We believe these factors can also be recognized in the Scottish Government’s definitions of child wellbeing.

Needs & Wishes

Research has concluded that children are more likely to feel positive when shared time arrangements are flexible, child focused and when they get a say in the details of those arrangements

Researchers therefore emphasise the importance of listening to children’s needs. For example considering how each parent’s work schedule coincides with the child’s school calendar.

But experts also highlight the importance of listening to the child’s wishes when determining a parenting plan.

Many warn against simply using a child’s wishes to make decisions. This can put a lot of stress and pressure on the child in a high conflict situation, by burdening a child to choose between parents. Also, McIntosh stresses that we shouldn’t always take a child’s wishes at face value, they must be put in the context of their developmental stage.

Child Inclusion In Dispute Resolution

For families dealing with conflict, child inclusive mediation may solve these difficulties by allowing a child’s wishes to be respected. Listen to Calm Scotland’s interview with Carol Hope to find out more.

This child inclusive approach has been found to lower shared parenting acrimony as well as benefiting parent-child relationships (especially with fathers) and positively impacting on a child’s long term emotional and psychological development.

Children’s Perspectives

It can be difficult to imagine what separation can be like for children. Watch Tom’s true story about his parent’s divorce below. Children Beyond Dispute can provide you with more information. Voices In The Middle also offers a platform for children from separated families to shares their stories.

Overnights with Young Children

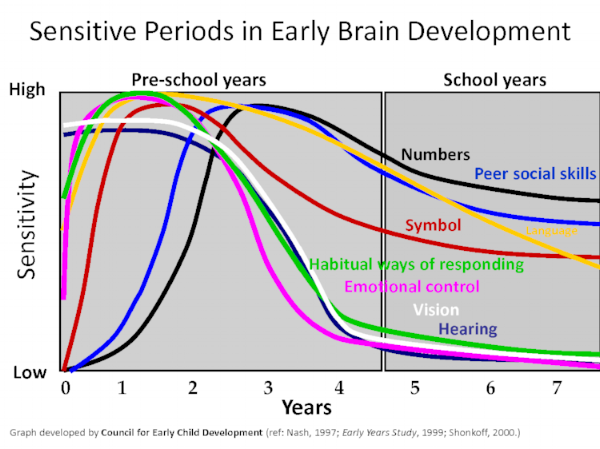

An enormous amount of brain development occurs during infancy (0-3 years old) (See the chart below) . For this reason, experts agree it is crucial that parenting arrangements provide a child with the best chances of healthy development.

Young Children In Divorce & Separation provides training programmes about early development and the needs of very young children in separation.

There is as yet no consensus on what is the best parenting arrangement. Some think it is beneficial for infants to have overnight stays at both parents’ houses, while others think this may cause too many risks. Long-term studies directly comparing different parenting arrangements for children raised in two houses from a young age are needed to help resolve what is the best arrangements. Read below for some details about ‘the case for’ and ‘the case against’.

The Case Against Overnights

The stance against overnights has principally been informed by John Bowlby’s attachment theory which suggests infants can have only one primary care giver and being separated from this caregiver can have adverse effects.

Australian research has found shared overnight care of young children, particularly infants, can negatively impact on the emotional and behavioural wellbeing of the child. However, these signs of emotional distress are not observed in children ages 4-5. It appears that by this age, most children are better developmentally prepared to do well in shared parenting arrangements.

Due to this, Sroufe & Mcintosh have suggested that equal numbers of overnights away from the primary carer should not occur before the age of 3.

The Case For Overnights

Neilsen has come forward criticising the methods used by previous studies that suggested these risks.

Evidence has also contested Bowlby’s original theory, leading researchers to conclude it is possible for infants to have a “multiplicity of figures for secure-base support”.

New empirical data demonstrates further evidence for the benefits of equal overnights. This research places emphasis on the long-term rather than short-term effects on parent child-relationships:

- Equal numbers of overnights (at each parents’ home) was associated with long term benefits for parent-child relationships with both parents

- Benefits in mother-child & father-child relationships were observed in overnights even when children were two years old and under the age of one

- These benefits were noticed regardless of whether parents initially agreed or disagreed about overnights

- Young adults who had more overnights with both parents felt closer to their parents and were more likely to remember their parents as having been warm and responsive during their childhood

Warshak’s review of the literature suggests it is favourable for young children to have an even balance of time and contact between the homes of separated parents.

He concludes that the considerations favouring overnights for most young children to be more compelling than concerns that suggest that overnights might negatively impact a child’s development.

He also argues that child developmental theory and data demonstrates that infants normally form attachments to both parents & long periods of absence threatens the security of the attachments between a parent and child.

A Middle Way?

McIntosh’s summary on the previous literature suggests that although studies support a caution about high frequency of overnight care for very young children, it also does not support arguments against any overnight care. This suggests is that the right amount of overnights is different in every family.

Researchers have argued healthy development in the young child depends on the capacity of caregivers to

- protect the child from physical harm and undue stress by being a consistent, responsive presence

- stimulate and support the child’s independent exploration and learning and the process of discovery

So, parents must provide both continuity in and an expanding care giving environment to ensure the secure development of their infant and where possible, organised caregiving with more than one caregiver is advantageous.

The following recommendations are suggested by McIntosh, Pruett & Kelly for determining if/how many overnights are beneficial for a child:

Factors In Deciding Levels Of Overnight Care

- The child’s safety with each parent, and parents safety with each other

- The child’s trust and security with each parent

- Parent mental health

- The young child’s health and development

- The young child’s behavioural adjustment

- Qualities of the co-parental relationship

- Pragmatic resources

- Family factors: extended and cultural

‘Gateway’ Assumptions

These must be met before moving onto deliberations about overnight time:

- The young child is safe with, and can be comforted by, both parents

- The young child is protected from harmful levels of stress.

If these are met parents should make plans that:

- Support the development of organised attachments to each parent/caregiver

- Encourage parenting interactions that support the development and maintenance of attachments with each parent

- Provide the young child with support to transition between parents

- Reflect practical considerations

- Maximise the amount of time the young child is cared for by a parent in person

- Encourage shared decisions about major child-related issues

Quality Vs Quantity

Many researchers have concluded that the quality of parenting is more important to children’s outcomes than the quantity of time spent with a parent.

However, it is important to note that sufficient contact time is needed to sustain close, quality relationships:

“To maintain high-quality relationships with their children, parents need to have sufficiently extensive and regular interaction with them, but the amount of time involved is usually less important than the quality of the interaction that it fosters” (Lamb, Sternberg & Thompson 1997)

Lamb, Sternberg & Thompson also suggest that both parents should be involved in the child’s everyday routine to allow them to play a psychologically important role in the child’s life.

So what does this mean for shared parenting?

- It may not be useful to create arrangements based purely on splitting time equally between parents, but that may be a useful starting point for discussions.

- Arrangements should ideally allow both parents to spend quality time with the child – including everyday aspects of their life.

- Regardless of quality or quantity of time spent, all arrangements should be adaptable to the child’s needs and the practicalities of the situation.