The International Council on Shared Parenting was formally constituted in Germany in 2014. Ian Maxwell, now retired as National Manager of Shared Parenting Scotland, was a founding board member.

The Council’s 7th International Conference took place in Lisbon last week, bringing together academics, civil society organisations, and family professionals, including lawyers, child psychologists and social workers. More than 230 participants from 34 countries attended either in person at the Law Faculty of the University of Lisbon or online.

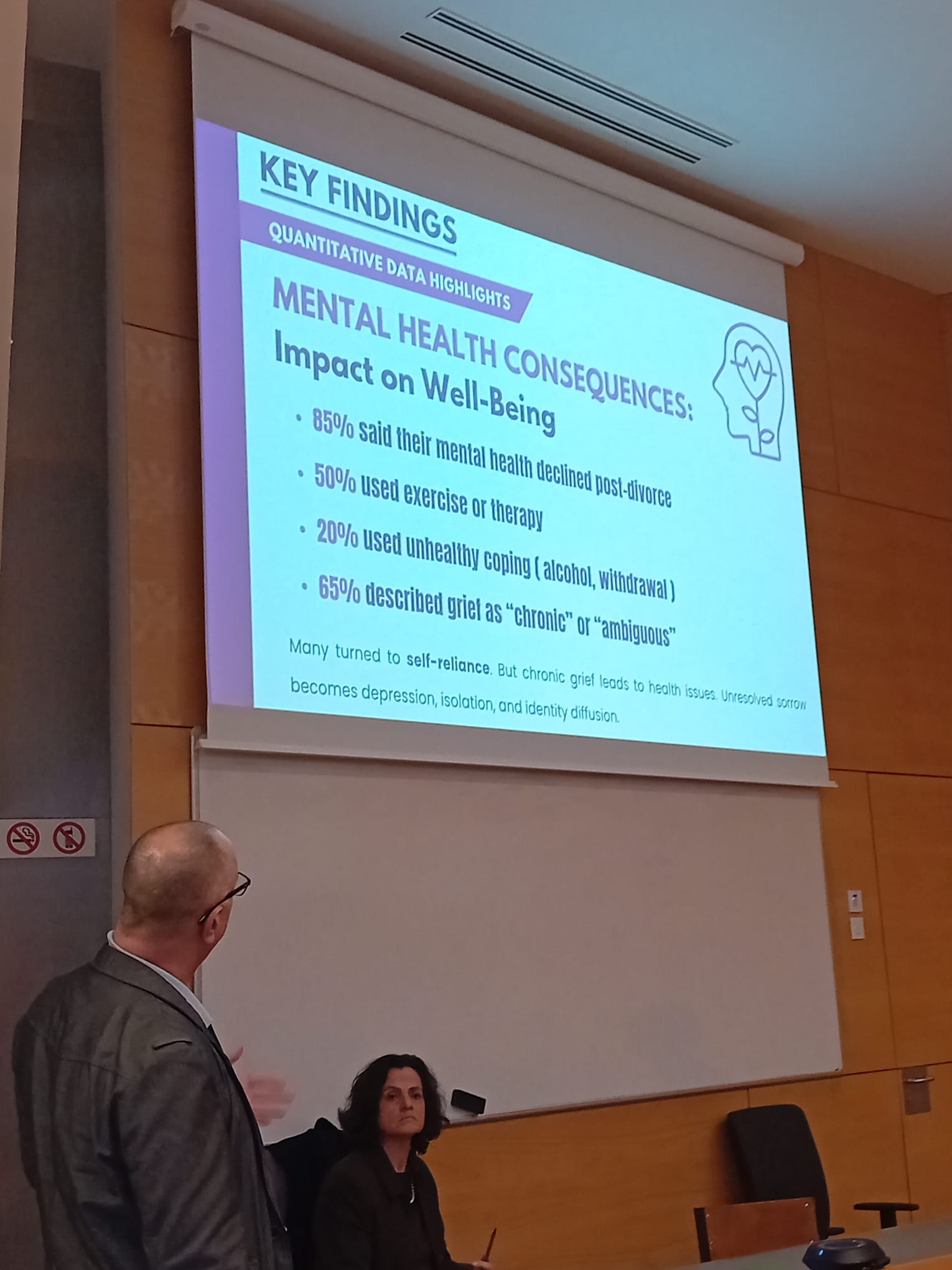

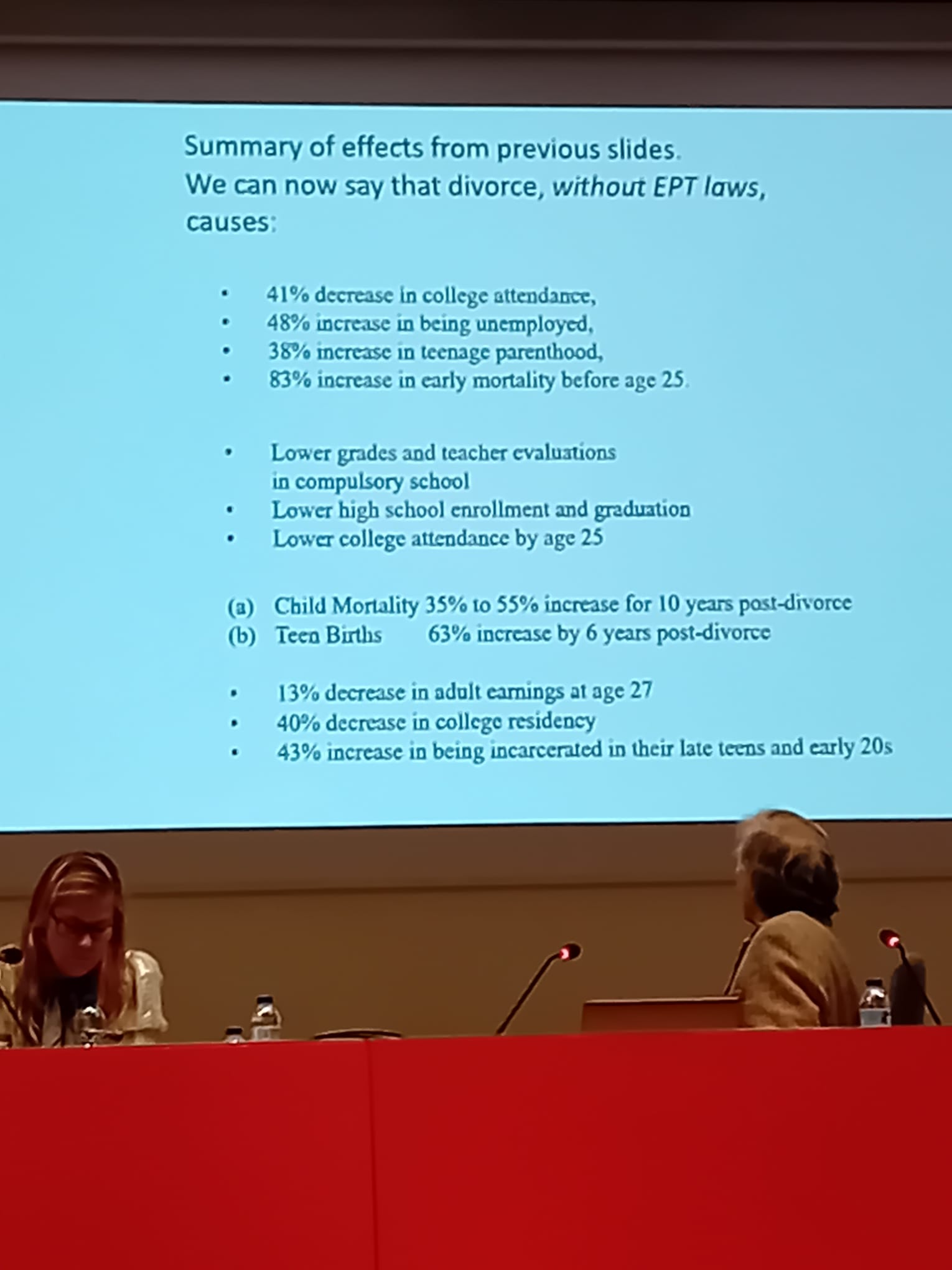

As a first-time attendee, I was most struck by the breadth, depth, and humanity of the discussions about the practical and legal consequences of divorce or separation for children, parents and wider families. The conference examined both individual physical and mental wellbeing but also the broader public health implications of how societies handle family transitions.

The breadth of intellectual curiosity underpinning research, insight, professional practice and policy development that is happening in jurisdictions around the world is in marked contrast to the wafer-thin boundaries imposed on debate in Scotland.

A central question throughout the conference was how to do the best we can for children affected by divorce or separation, recognising, as one workshop put it, that “when a family reorganises, it’s not just the structure that changes, but the child’s inner world”.

ICSP President Edward Kruk, Emeritus Professor of Social Work at the University of British Columbia, opened the conference by emphasising the organisation’s focus on developing “evidence-based recommendations about the legal, judicial and practical implementation of shared parenting … as the cornerstone of healthy child development, and as a fundamental right of children, along with the need for protection from harm, safety and security”.

“Changing the argument” was a major theme of the programme, with speakers drawing on academic research and population-level data to challenge policymakers’ continued reliance on assertion or isolated anecdote – approaches in which children’s own experiences are often overlooked or constrained.

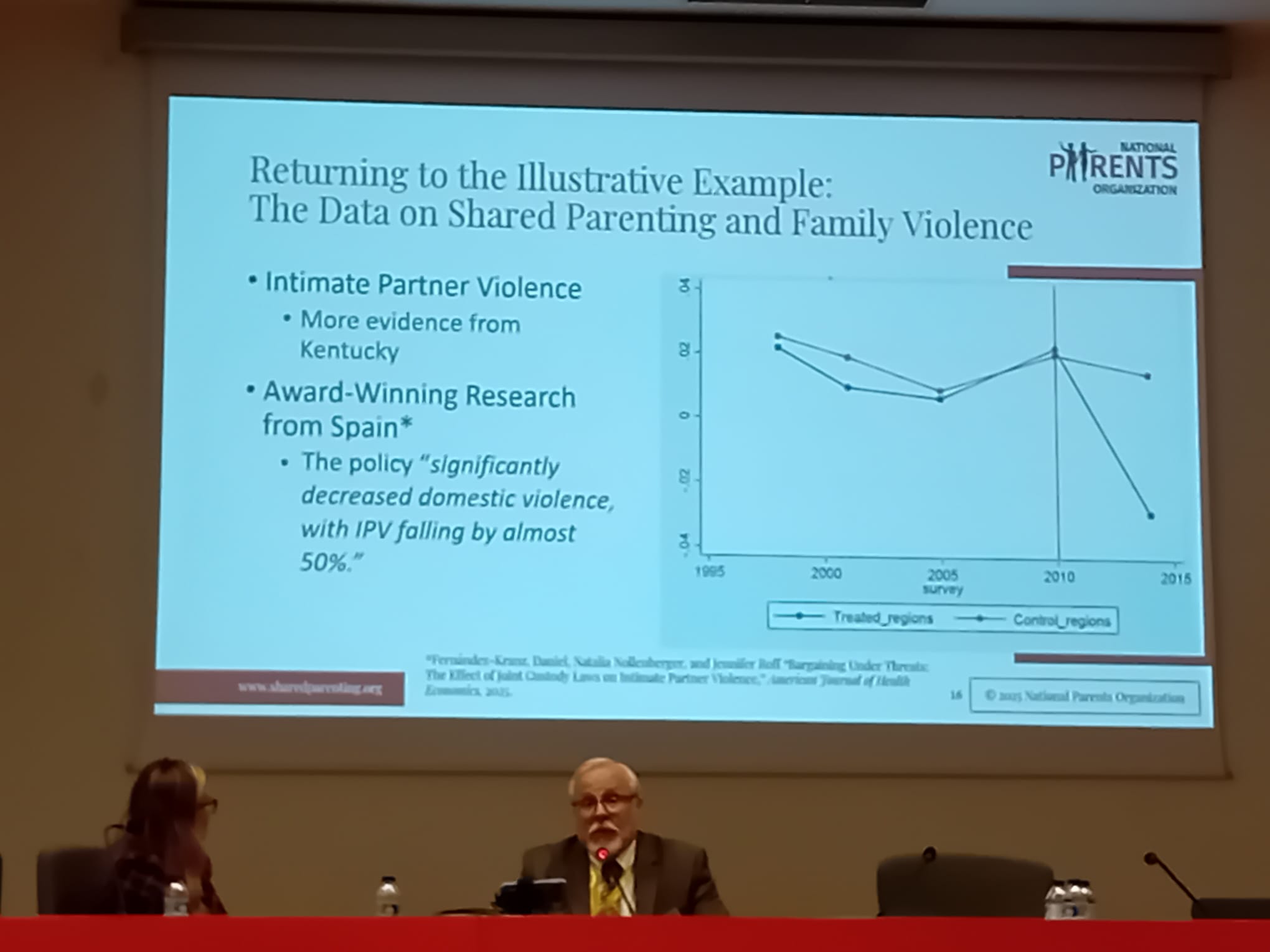

Don Hubin, President of the US National Parents Organisation, presented research showing dramatic reductions in allegations or reports of domestic violence in states that have introduced a rebuttable presumption of equal shared parenting.

Edward Kruk similarly explored evidence that shared parenting can act as a protective factor against domestic violence affecting children.

William Fabricius, Associate Professor of Psychology at Arizona State University, has published extensively on the lifelong neurological impact of conflict on children. He presented new research from Spain showing that seven provinces which enacted equal parenting legislation recorded significant reductions in reports of parental conflict. Five neighbouring provinces without similar legislation showed no such reduction.

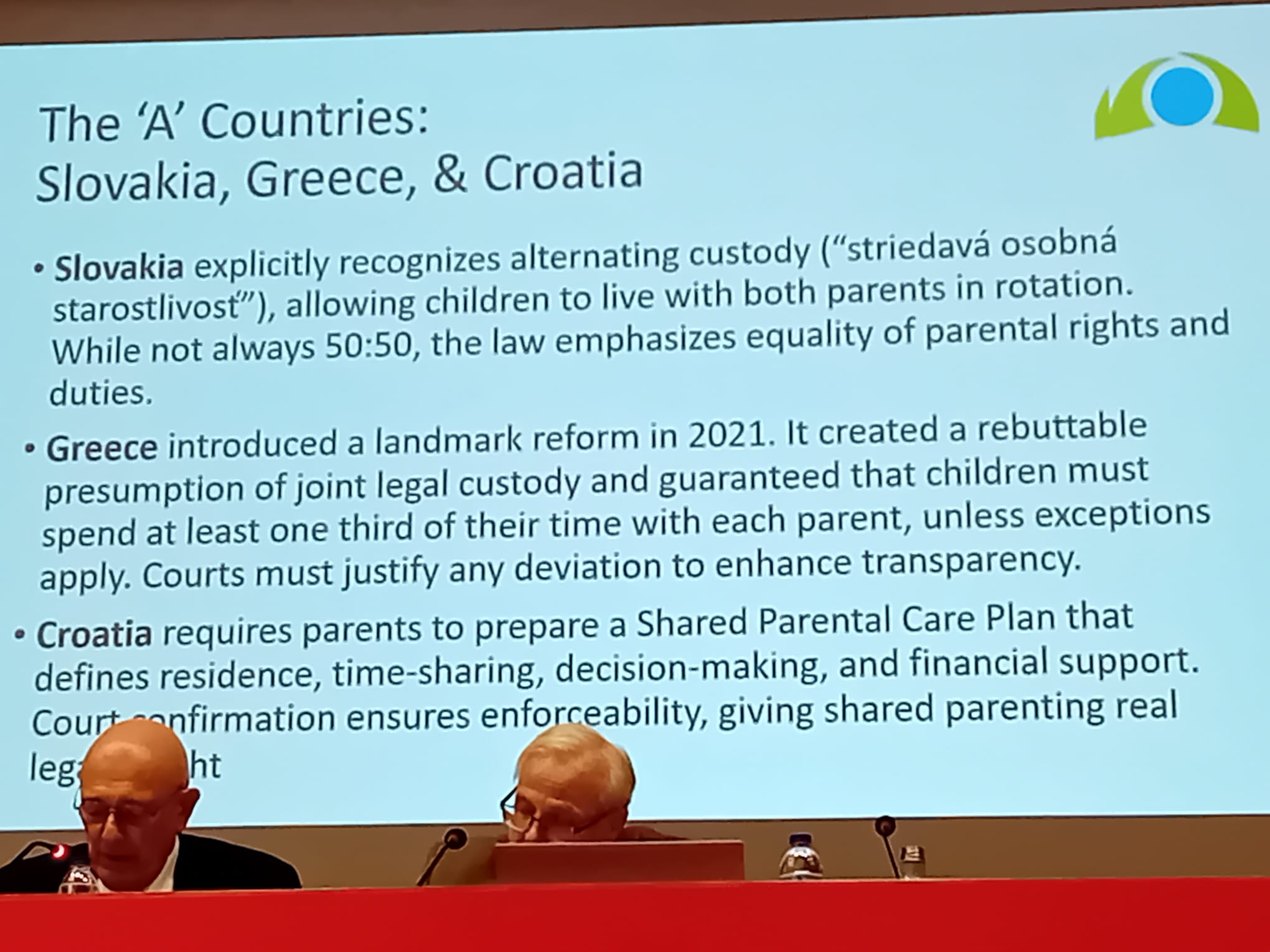

There is no silver bullet that resolves shared-parenting issues in every situation or every jurisdiction. But the debate itself, when grounded in evidence, is live, evolving and constructive. Most reasonable people agree that the goal must be the best interests of the child.

One of the most striking insights in Lisbon came from a Polish academic who asked 40 family court judges to define “the best interests of the child” and received widely differing answers.

Scotland would benefit from greater academic and policy curiosity, better transparency in decision-making and a willingness to unbuckle the straitjacket that currently constrains fresh thinking about how best to support our children.

Remember, we have an aspiration for Scotland to be the best place for children to grow up. It also needs to be the best place to be a parent.